We've joined our RTI Health Solutions colleagues under the RTI Health Solutions brand to offer an expanded set of research and consulting services.

In the US, health observers have long touted the benefits of community health workers (CHW). Their pivotal role in the COVID-19 pandemic, though, further spotlighted the ability of these professionals to reach historically marginalized communities and address social determinants of health in times of crisis.

Now, a growing body of research is exploring the benefits of using these essential workers in everything from improving primary care access to helping ease formerly incarcerated people back into society. More broadly, health experts, policy makers, and researchers are calling for the expanded use of CHWs as a way of addressing the country's widespread health inequities.

“Community health worker programs—long heralded as a best practice for reducing health disparities—reflect the core tenets of health equity interventions," according to the authors of an article published in JAMA Health Forum.

Who are community health workers?

CHWs work on the front line of public health, liaising between medical and social services. As lay members of the community, CHWs may work for pay or serve as volunteers with the local health system. They hold a variety of titles like health coach or community health advisor.

Often, CHWs share ethnicity, socioeconomic status, language, or cultural backgrounds with the communities they serve. Along with culturally-appropriate health education, CHWs may also help people access and understand healthcare options and community social supports—and can advocate for community needs in a broader setting.

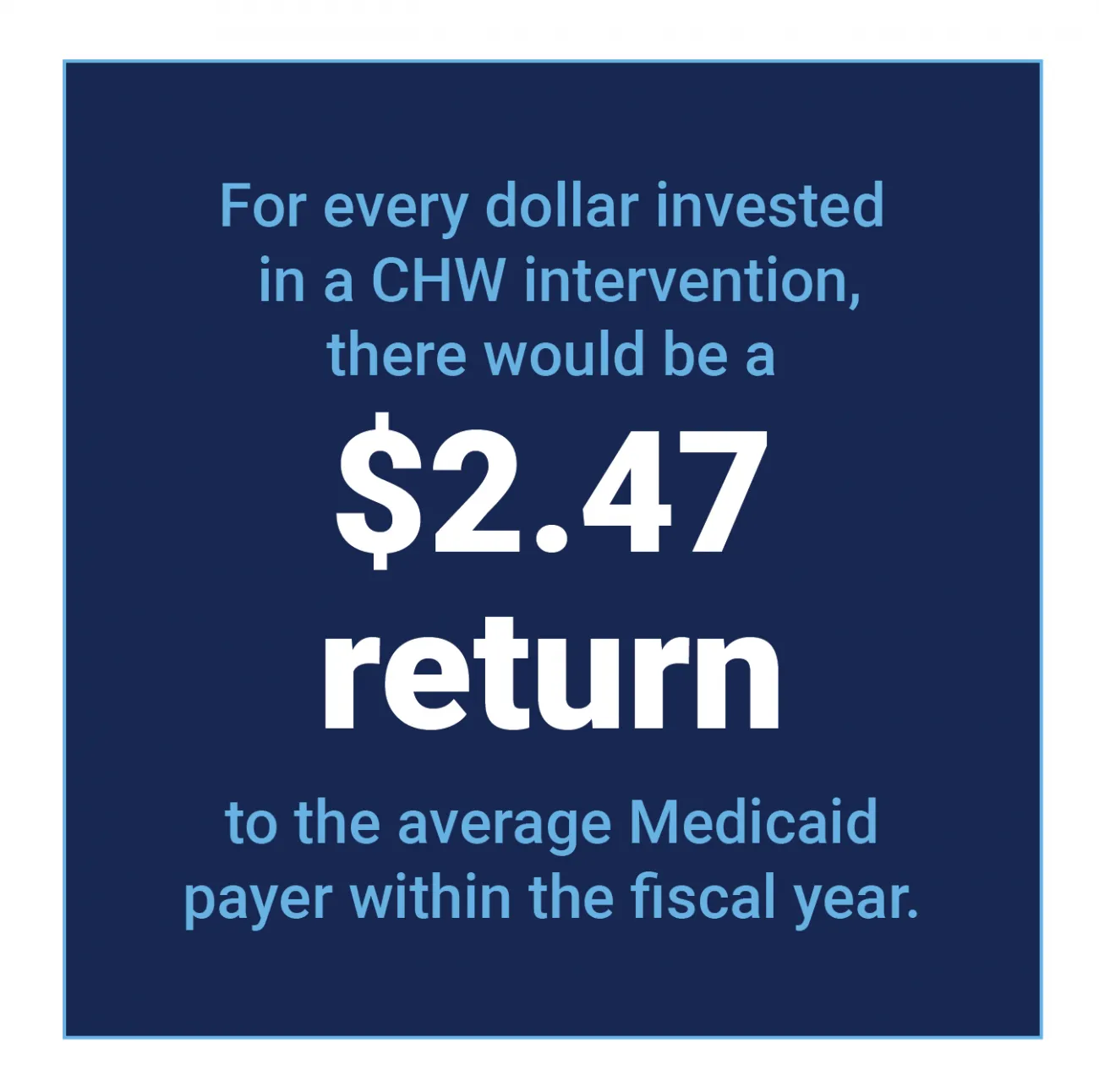

Research has repeatedly demonstrated the benefit of deploying these professionals in a variety of situations, from aiding diabetic patients in improving sugar control to reducing hospitalizations by connecting people with medical and social supports. Other reports have pointed to the cost savings involved in such programs, such as a Health Affairs-published report that found for every dollar invested in a CHW intervention, there would be a $2.47 return to the average Medicaid payer within the fiscal year.

Figure 1: CHW intervention return on investment

Pandemic underscores key role of community health workers

Throughout the world, the pandemic highlighted the critical role of CHWs, especially for their efforts aiding COVID-19 vaccination and outreach efforts. These steps helped improve access and information in under-represented communities, notes a review article published in Global Health: Science and Practice.

The pandemic experience also underscored the importance of better integrating CHWs into the system as formal health workers. As attention on CHWs increases, it's important to ensure that they receive adequate payment, supervision, and support as well as access to transportation, the publication noted.

Building trust, offering cultural concordance

In the US, there are more than 60,000 CHWs, according to data from the US Bureau of Labor Statistics, though some observers say this is likely an underestimation.

CHWs bring an element of cultural concordance to the healthcare system especially in areas where it is difficult to recruit and retain providers and caregivers that represent the communities they serve. These relationships are a crucial aspect of efforts to reduce health inequities and expand access for historically marginalized populations.

Since the CHWs often share backgrounds with the people they serve, the relationships can transcend historic mistrust of medical institutions.

Research offers useful takeaways

For example, a newly-published study found promising results when using CHWs to build medical trust with high-risk rural residents. The research, published in the Journal of General Internal Medicine, looked at strategies CHWs used to build trust with rural Idaho participants who received health screenings at food banks and pantries.

Among that study's findings:

- CHW programs are important for building trust in low-trust populations

- Trusted organizations with community ties can serve as vital partners that might provide the only opportunity to reach some community members

- Significant time and resources are necessary to build interpersonal trust during the initial outreach stage

- Strengthening infrastructure that supports CHWs is important. For example, closing a facility such as a food bank can interfere with CHW connections in underserved communities

- Healthcare and government institutions should be cautious when partnering with trusted community organizations since their very involvement could transfer that institutional mistrust

Deploying formerly incarcerated CHWs

Another innovation comes from using CHWs to help the millions of individuals transition back to their communities after incarceration, an approach described in the Better Care Playbook. States are increasingly looking at ways to expand Medicaid coverage and care for this population, which faces a disproportionate burden of both physical and behavioral health conditions.

Under this model, a national network of primary care clinics, which supports post-incarceration re-entry, works with CHWs who have been previously incarcerated themselves. The collaboration has reduced avoidable acute healthcare utilization as well as had a positive impact on criminal/legal system involvement. At the same time, the partnership provides for more seamless post-incarceration care transitions.

School-based interventions hold promise & challenges

Evidence of promising interventions is also coming from the use of CHW in school settings for both children and parents, efforts described in a literature review published in 2023 in Academic Pediatrics. Programs that use CHWs encompass a broad range of topics and efforts, from violence prevention to resilience development to obesity, smoking cessation, and drug and alcohol abuse. Others addressed community, which engagement and parental involvement in schools.

While these interventions are promising—a majority found positive outcomes for children and/or parents—the review highlighted a key challenge. There was a lack of consistency especially when it came to CHW recruitment, training, and roles. Authors suggested a standardized reporting mechanism for these school interventions, which could pave the way for reproducing and scaling up interventions that work and documenting best practices.

Public health, government support and interest growing

As evidence of the value of these CHW programs grow, policymakers are investing more resources and support.

In 2022, the Biden Administration announced $225 million in American Rescue Plan Funding that would be used to train 13,000 CHWs. The Consolidated Appropriations Act of 2023 built on that momentum, allocating $50 million each year to boost the CHW workforce from fiscal year 2023 through 2027.

That law directs future funding toward CHWs who provide education and outreach to medically under-served communities and other at-risk populations, explains the Georgetown University Health Policy Institute. This includes people who live in geographic areas that might require extra support during a future public health crisis.

More states using CHWs in Medicaid programs

Evidence of this growing support and interest is also evident in state Medicaid programs that provide coverage for CHWs. A 2023 Kaiser Family Foundation report describes the following developments:

- States are increasingly allowing Medicaid payment for services provided by CHWs

- Some states are targeting CHW interventions to pregnant and postpartum interventions

- Several states reported plans to introduce new certification or standardized training programs

- Some states are working to identify best practices for expanding CHWs and supporting broader acceptance by Medicaid providers, health plans, and beneficiaries

Paving the way for broader primary care approaches

While some states' Medicaid programs use CHWs to target care management for specific populations, others are looking to more broadly serve the Medicaid population, explains The California Healthcare Foundation. In California, for example, CHW are considered part of preventative health services, including health education and help navigating the healthcare system.

Similarly, Indiana's program includes direct preventative services or services aimed at slowing chronic disease progression. And, in Louisiana, people who qualify can be eligible for health promotion and coaching, including screening for health-related social needs.

Standardizing CHW credentials

As deployment of CHWs expands, licensure remains an area of interest and will require future attention. As of the date of this article, no national standard for CHW certification exists, although states have developed robust training courses, certification programs, and other forms of oversight.

It is important that credential requirements do not limit the ability to hire members of of the community, who may not have the same access to formal education as those from outside of the community. In-house recruitment and training programs can entice participation from members of the unserved community and also promote a career pathway in places where jobs may be scarce.

Using a health equity lens for future growth

As investment and support grow, so does the need to address CHWs own personal and professional needs and growth, point out the authors of the JAMA Network report. That translates into strengthening employers' institutional capacity to be responsive to these needs.

Those strategies build on prior research describing the importance of promoting CHWs as “legitimate partners" that provide support to healthcare teams and patients, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Organizational support may come in the form of having team meetings, training opportunities and access to electronic health records.

Valuing and supporting CHWs

Indeed, too often CHWs face low wages and a lack of career advancement opportunities. That in term contributes to turnover, attrition, and broader workforce instability, according to The Center for Community Health Alignment, part of the Arnold School of Public Health at the University of South Carolina.

Educating other healthcare professionals about their critical role is a step in decreasing this attrition. Higher wages and more training opportunities could help, too. And, when considering career advancement, it's important to value lived experiences over formal education, the brief noted.

Indeed, it's important to recognize and value CHWs, individuals who are making considerable strides in promoting health and narrowing access and outcome inequities.

RTI Health Advance can help create health interventions

At RTI Health Advance, we can help you create evidence-based strategies that create better interventions for at-risk populations. Our team of health experts utilizes the latest peer-reviewed research and strategies to reduce barriers and improve access to equitable care.

Subscribe Now

Stay up-to-date on our latest thinking. Subscribe to receive blog updates via email.

By submitting this form, I consent to use of my personal information in accordance with the Privacy Policy.