We've joined our RTI Health Solutions colleagues under the RTI Health Solutions brand to offer an expanded set of research and consulting services.

Closing The Gap In Delivering Equitable Care For Serious Illness

Living well with serious illness and experiencing person-centered end-of-life care (or a "good death") is supported through palliative care, hospice services, and a holistic philosophy of care. While palliative and hospice care have expanded nationally and are more integrated into the fabric of healthcare, inequities are creating barriers for people from historically and economically marginalized groups.

Explore the unique needs of individuals living with serious illness and the barriers we must overcome to deliver beneficial, advanced care — improved pain and symptom control, better care at home, longer lifespan, less distress, and more time for personal priorities.

What is serious illness or life-limiting illness?

The Coalition to Transform Advanced Care (C-TAC) defines serious illness (aka advanced illness or life-limiting illness) as "occurring when one or more conditions become serious enough that general health and functioning decline and treatments begin to lose their impact. This is a process that continues to the end of life."

Our Executive Vice President, Dr. Amy Helwig, recently presented on a panel at the C-TAC Summit on closing the gaps to equitable care related to serious illness.

Palliative and hospice care share aims with important differences

About 40 million people in the US experience limitations due to serious illness. Many individuals living with advanced illness receive disjointed, hospital-based care via a patchwork of specialists that may not align with their personal, cultural, religious, or familial goals and preferences.

Hospice and palliative medicine (HPM) became a recognized specialty by the American Board of Medical Specialties (ABMS) and the Accreditation Council of Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) in 2006.

Both palliative and hospice care have common aims: providing comfort to help with pain or symptom control, offering a whole-person approach, and tapping into services outside the traditional medical model, like pastoral care. However, palliative care and hospice focus on different phases of the patient's journey. Palliative care can be engaged when a person is first diagnosed with a serious, potentially life-limiting illness. It can provide comfort care while also delivering treatment intended to cure. Hospice offers comfort care only for individuals diagnosed with a terminal disease, and their doctor believes the patient has six months or less to live. In most cases, hospice does not provide curative treatment.

Palliative and hospice care help people live better and sometimes longer

A Veterans Affairs study published in JAMA found that patients diagnosed with advanced lung cancer who received palliative care had a higher quality of life with serious illness and lived longer. Other studies have confirmed the same: The New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM) published a three-year study, concluding that patients who received palliative care upon diagnosis lived nearly three months longer, were happier, more mobile, and experienced less pain.

Another study revealed that the team- and home-based, coordinated, and holistic care patients received through hospice services reduced hospital days by 1,361 per 1,000 people, reduced dying in the hospital by 8.2%.

Disparities in palliative and hospice care for serious illness

Palliative and hospice care have taken many years to grow as a specialty, gain acceptance by referring clinicians, and overcome confusion with practitioners and the public. But, even with greater acceptance and understanding, many historically underserved patient groups are not receiving palliative care or hospice care at the same levels as other groups nor receiving the option or information to make a choice.

White patients are 10 times more likely to use or have access to hospice than BIPOC patients. Race, ethnicity, gender, geography, socioeconomic and insurance status influence access and awareness of the benefits of palliative and hospice care:

- Populations who are Black, Hispanic/LatinX, Indigenous, LGBTQ+, rural, and low-income suffer disproportionately in the face of serious illness.

- These same communities experience more diagnoses in the later stages of an illness and have fewer options for care support, thus increasing the likelihood of inferior outcomes.

- ~82% of hospice patients are White, 8.2% Black, 6.7% Hispanic, and 3.1% other races/ethnicities (NHPCO, 2018).

- 2-3 million US adults with low incomes live in states that did not expand Medicaid and do not have access to palliative care/hospice benefits.

- 1:3 hospice programs limit or do not treat undocumented immigrants.

- Hospice and PC are also often inaccessible for American Indians/Alaska Natives.

- Many tribal health organizations are unable to meet Medicare/Medicaid requirements for hospice services.

Addressing gaps in palliative and hospice care

Improving access for rural communities and historically under resourced populations

According to a report, titled National Review of State Palliative Care Policies and Programs, palliative care professionals, resources, and services are limited in smaller towns and rural communities. If rural community organizers of healthcare organizations can't bring large-scale palliative care and hospice services to the region, an alternative is to train nurse practitioners.

Research has shown that nurse practitioners are cost-effective, resourceful, and successful in responding to needs similar to those of people with advanced illnesses. Nurses were also helpful in recognizing palliative care needs and recommending consultations. Educating and implementing community health workers can also provide some level of service in areas that don't have ready access to clinical services.

Dr. James Joseph, Medical Director at Geisinger Hospice, points to innovative ways to deliver hospice care in geographically underserved communities. These include digital health technologies like telemedicine, partnerships with rural organizations and non-profits, and additional training for rural clinicians. Volunteers can also be trained to provide a host of needed, non-medical supports like respite care, groceries, visitations, grief support, companionship, and transportation to appointments.

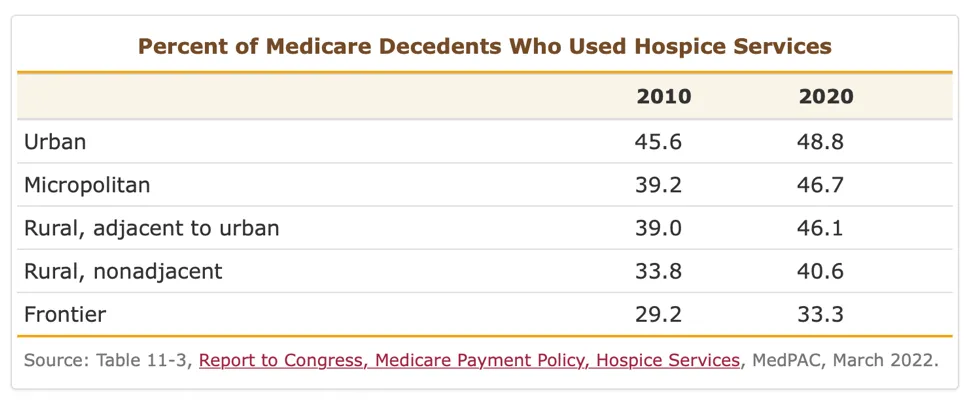

Figure 1 shows growth in hospice service usage in rural communities but a continued disparity in urban and micropolitan areas.

Palliative and hospice care awareness

There are a host of myths and misconceptions about palliative and hospice care. For example, a 2020 published study found four erroneous beliefs among U.S. adults who reported knowing about palliative care:

- 44.4% automatically thought of death when asked about palliative care

- 38.0% equated palliative care with hospice

- 17.8% believed you must stop other treatments when seeking palliative care

- 15.9% saw palliative care as giving up

While physician knowledge around palliative and hospice care has improved, many misconceptions remain, particularly around how and when to discuss care options with patients from historically marginalized populations. According to a 2021 study, "Gaps in understanding and the ability of nurses and physicians to communicate end-of-life issues, introduce palliative care services to patients and their families, and confront sociocultural issues suggest the need for a longitudinal training program."

Cultural humility and broaching serious illness topics

In general, illness, disability, and death are proscribed subjects. However, for some cultures, speaking of death may have a more profound negative impact. Further, if a person is facing a life-limiting illness and their family caregiver does not want palliative and hospice care, providers should respect their decision.

For example, Black and Hispanic patients spend 32% and 57% more than White patients in the last six months of life. Similar differences exist within genders, age groups, causes of death, location of death, and in similar geographic areas. 85% of higher costs for non-Whites are due to greater end-of-life use of the ICU and various intensive procedures; 35% is due to life-sustaining interventions.

An article in The Atlantic, written by Ibram X. Kendi, explains, "But the space between adequately treating illness and planning for, and finding, peace when the end is near can be full of trepidation, particularly for those who understandably don't trust that their very lives are valued or 'expected'."

Patient and family engagement and communication can highlight the benefits of these supportive services and how they can improve the quality and length of life without taking away their ability to make treatment decisions, particularly with palliative care. However, culturally-sensitive language and treatment approaches are critical, and training should emphasize this. Palliative and hospice medicine is well-suited to address because it was built upon a person-centric approach to holistic care.

Palliative care is not about giving up. As Dr. Erin Kross, Co-Director of the Cambia Palliative Care Center of Excellence at UW Medicine, approaches it, "When people are diagnosed with a new serious illness or a life-limiting or terminal condition, we have a basic conversation about what is most important to them, what do they really value, and what are their main priorities in life. Then we help map out how that interfaces with a treatment plan."

Self- and provider-advocacy when dealing with serious illness

When patients or their families have concerns that they or their loved one is suffering too much, or facing mounting distress from unresolved symptoms, they should be empowered and provided information to request a palliative care consultation. This is notably lacking when it comes to non-White patients.

Physicians have been shown to deliver less information and communicate less support to Black and LatinX patients compared to White patients. Additionally, patients from historically marginalized groups often do not receive treatment consistent with their wishes, even when they have been communicated. A provider's culture, religion, and ethnicity also influence their decision to explain palliative care to patients or to encourage a consultation.

Encouraging self-advocacy, pointing patients or their families to educational resources, and reinforcing that symptom control is vital to living well while facing any serious illness are central to the value of palliative and hospice care.

Break down the barriers to equitable palliative and hospice care for serious illness

Our team of clinicians, data scientists, healthcare operations, and digital health experts support innovative programs and services to make care more equitable, cost-effective, and high-quality. Contact us to discuss the needs in the communities you serve.

Subscribe Now

Stay up-to-date on our latest thinking. Subscribe to receive blog updates via email.

By submitting this form, I consent to use of my personal information in accordance with the Privacy Policy.