We've joined our RTI Health Solutions colleagues under the RTI Health Solutions brand to offer an expanded set of research and consulting services.

Overlooked Americans: The Toll Of Chronic Disease In Rural America

Rural Americans face disproportionately high risks when it comes to chronic disease, the country's leading cause of death and disability. Limited access to healthcare services and an array of long-standing socio-economic challenges are among the primary contributors to rural health disparities.

For the 60 million people living in rural areas – about 19% of the U.S. population – the odds of dying prematurely from chronic illness are significantly higher than those faced by their urban counterparts. Primary chronic disease killers include:

- Heart disease

- Cancer

- Chronic respiratory disease

- Diabetes

- Stroke

Despite multiple government initiatives aimed at addressing rural health disparities, the health gap between rural (defined as less than 2,500 residents) and urban residents continues to expand. At least one expert believes rural health disparities reflect a structural bias toward urban populations, one that can only be resolved by reimaging healthcare as community infrastructure, much like a public utility.

Rural health disparities - One nation, divided

Statistics illuminate the stark health divide between urban and rural residents:

- Across the spectrum of chronic disease conditions – high cholesterol, high blood pressure, obesity, arthritis, depressive disorder, diabetes, COPD, and heart disease – prevalence of illness is higher in non-metropolitan than metropolitan areas.

- According to one study, 54% of rural patients with COVID-19 died within 30 days of being admitted to intensive care, compared to just 30% of patients in large urban centers.

- While the rate of overall diabetes deaths decreased in the US between 1999 and 2019, the diabetes-related mortality gap between rural and urban populations nearly tripled over the same period. Mortality is particularly high among men living in the rural south.

- Disparities between rural and urban residents in illness-related rates of death per-100,000-population are similarly pronounced for chronic lower respiratory disease (38% higher), heart disease (17% higher), stroke (15% higher), and cancer (10% higher).

- Life expectancy for rural men is 3 years less than their urban counterparts (77 versus 80 years) and 2.7 years less for rural women (79.7 versus 82.4 years).

Greater distances, fewer options for rural healthcare

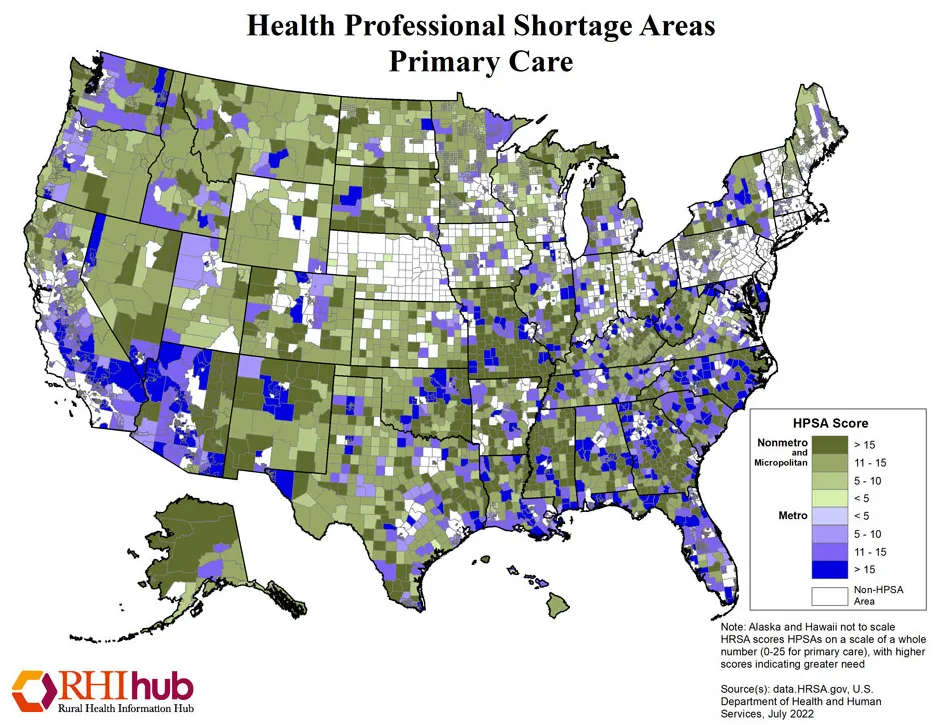

Chronic diseases' grip beyond the cities and suburbs stems in part from the inherent isolation of rural life. The ready access to care most urban residents take for granted is often the exception for those living in rural areas. Case in point: the patient-to-primary care physician ratio in rural areas is just 39.8 physicians per 100,000 people, versus 53.3 physicians per 100,000 in urban areas. See Figure 1.

Isolation frequently makes it a challenge to sustain ongoing care. Rural women with breast cancer, for instance, can travel up to 2,000 miles over the course of their treatment, with the closest radiation facility for rural patients averaging 22 miles away, compared to 4.8 miles for urban patients. Given that patients typically receive radiation as frequently as 5 times a week, the miles can quickly add up.

Another study found that travel time to hospitals averaged 17 minutes for rural residents, versus 12 minutes in the suburbs and 10 minutes in urban areas. Travel problems can be compounded by limited or non-existent public transportation and poor road conditions.

Figure 1: Health Professional Shortage Areas in Primary Care, Rural Health Information Hub, July 2022.

Rural healthcare workforce shortage

Healthcare workforce shortages add another layer of scarcity, with less than 8% of all physicians and surgeons choosing to practice in rural settings. Specialty and subspecialty care, as well as advanced diagnostic technologies, are less likely to be available in rural counties, and those providers who live and work in rural areas frequently have less education and training.

The challenges of accessing care are reflected in lower screening rates among rural versus urban residents when it comes to cholesterol (80.3% v. 87.2%), cervical cancer (81.3% v. 87.3%), and colonoscopies (58% v. 61.3%). Rural residents also have lower access to health information from physicians, blogs, websites, government agencies, magazines, and radio.

A matrix of social determinants

Against this backdrop of often-problematic access and reduced health literacy, rural residents face a complex mix of social determinants that collectively increase the likelihood of chronic disease onset. Rural residents are more likely to have low-to-moderate income; the poverty rate in rural America in 2019 was 15.4% versus 11.9% in urban areas. A report by the Kaiser Family Foundation found that rural residents, as a group, are:

- Less likely to have employer-sponsored health insurance

- More likely to be elderly

- More likely to have Medicaid or another form or public health insurance

- More likely to be unemployed

Rural residents also are less likely to have higher education. They're at greater risk of fatal car crashes, suicide, and drug overdoses. In addition, many industries in rural areas are associated with greater risk for chronic disease. These include mining and resulting respiratory illnesses, as well as the risks of extended exposure to chemicals and sun that can come with a career in agriculture.

Sustaining a healthy diet likewise is a problem. As the National Institute for Health points out, rural Americans often live substantial distances from grocery stores, with convenience stores the only nearby food option. Because convenience stores tend to carry fewer fresh fruits and vegetables and instead stock many processed foods that typically are high in salt, sugar, and fat, diet-related health problems like heart disease, diabetes, and obesity may be exacerbated.

As significant as the chronic disease risks are for rural Americans generally, they're even more pronounced for minority and ethnic populations, with rural BIPOC having higher incidences than their White counterparts of multiple chronic diseases (40.3% vs. 36%) and obesity (45.9% and 38.5%, respectively, vs. 32%).

Expanding the reach of telehealth

One of the few silver linings to emerge from the pandemic has been the explosion of telehealth services, which have helped some rural providers maintain support for chronic disease patients. Yet telehealth capabilities are largely unavailable in the nearly 40% of rural counties without broadband internet. The good news is that the federal bipartisan infrastructure law signed by President Biden last November provides $65 billion to help states build out high-speed infrastructure for the approximately 30 million Americans that currently cannot access high-speed internet.

Other initiatives and resource centers aimed at addressing rural health disparities include the following:

- The administration recently announced $110 million in U.S. Department of Agriculture grants to help 208 rural health organizations expand critical services to nearly 5 million people in 43 states. The money will be used to improve access to care and services in rural areas by helping to build, renovate, and equip hospitals and clinics.

- On October 17, President Biden signed the MOBILE Health Care Act, which will provide community health centers with funding flexibility to establish mobile health delivery clinics that will increase access in rural communities that don't have sufficient population to support full-time health centers.

- The Rural Health Information Hub offers guidance on model rural health programs, overviews of successful projects, and evidence-based tool kits that help communities develop and implement rural initiatives.

- The National Rural Health Association (NRHA) serves as a clearinghouse for leadership, ideas, information, communication, research, and advocacy related to improving rural health and reducing disparities.

A comprehensive state approach to rural health disparities

In recognition of the many structural and social issues that collectively contribute to health and chronic disease disparities, the South Carolina Office of Rural Health in 2017 set out to develop a long-term roadmap to improve healthcare for the state's 1 million+ rural residents.

A broad task force that included leaders from healthcare, business, education, government, and community organizations worked to create a strategic plan focusing not only on improving healthcare access, but also enhancing community leadership and engagement, economic development, education, and housing.

As the task force noted, “While shoring up the healthcare delivery system in rural South Carolina is paramount, there is also recognition that multiple social determinants of health, such as affordable housing, access to healthy food, transportation, quality schools, and viable employment are highly correlated to positive health outcomes and must be addressed concurrently in order for any real progress to be made."

Implementation of the plan began in 2019 and has initially focused on improving rural-urban health equity by working to achieve broadband connectivity and digital literacy in all communities across the state.

Structural urban bias

As important as such comprehensive efforts are, one expert believes the higher incidence of chronic disease among rural Americans can never be fully addressed without making fundamental structural changes in the healthcare system itself.

Janice Probst, PhD, is the associate director of the Rural & Minority Health Research Center at the University of South Carolina's Arnold School of Public Health. Probst has studied rural healthcare for 30 years and has coined the term “structural urbanism" to describe how the current healthcare system is financially skewed to benefit urban populations at the expense of rural residents.

Probst and fellow researchers define structural urbanism as a bias toward large urban centers stemming from:

- Healthcare's market orientation, which necessitates a critical mass of paying customers to make services viable

- A public health focus on changing outcomes at the population level, which differentially allocates funding toward large population centers

- The innate inefficiencies of low-population and remote settings, in which even equal funding can never translate into equitable funding

The system's predisposition toward populations versus communities is reflected at multiple levels in healthcare funding, Probst says, most notably through Medicare and Medicaid's focus on providing financial resources to individuals but not infrastructure.

“As a result," Probst wrote in Health Affairs, “communities with large populations that can yield revenue have flourishing health care institutions, while those with fewer residents have lost ground. The current health care funding model, whether targeting high need and high-number populations or focusing on more efficient payment arrangements, is still focused on individual patients, which creates an implicit bias toward large, generally urban populations and institutions."

Healthcare as infrastructure

To solve the problem, Probst argues, the US must redefine healthcare as a common good and support in much the same way that it does roads, utilities, and other public infrastructure. She acknowledges that making this transition would not be simple, given the inherent complexities of healthcare funding and the predominant influence of market forces. Nonetheless, conceptualizing rural healthcare as infrastructure can provide a path to permanent funding, through whatever mechanisms can be designed.

“Until we stop viewing healthcare as an optional purchase, like me buying mascara so I'll look good at a conference, we're not going to solve the problem," she said. “I think we have to have a shift in perspective that says, `Healthcare is a utility essential for the survival of a community.'"

Learn more

RTI Health Advance works with healthcare organizations to support rural healthcare initiatives advancing equitable care leading to better health outcomes. Use the form on the Contact page to get in touch with a member of our team today.

Subscribe Now

Stay up-to-date on our latest thinking. Subscribe to receive blog updates via email.

By submitting this form, I consent to use of my personal information in accordance with the Privacy Policy.