We've joined our RTI Health Solutions colleagues under the RTI Health Solutions brand to offer an expanded set of research and consulting services.

Identifying Health Inequities Experienced By Disabled Persons

Over 30 years ago, the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) changed the trajectory for millions of Americans living with disability. The intervening decades have unfurled material changes, such as: curb cuts, disability parking and seating in public facilities, bus lifts, more accessible telecommunications, and laws to support fair employment practices. Recognizing these changes, though, many Americans with disabilities continue to face deep, longstanding health inequities, including barriers to care, lower quality of care, and disparate health outcomes.

With a population of 61 million adults and 3 million children, representing 28% of Americans, persons with disabilities comprise the largest subpopulation in the US, reflecting all races and ethnicities. At a time when health equity conversations,requirements, and plans are ramping up positive change, persons living with physical, behavioral, or sensory disabilities should be included in the movement for more equitable healthcare.

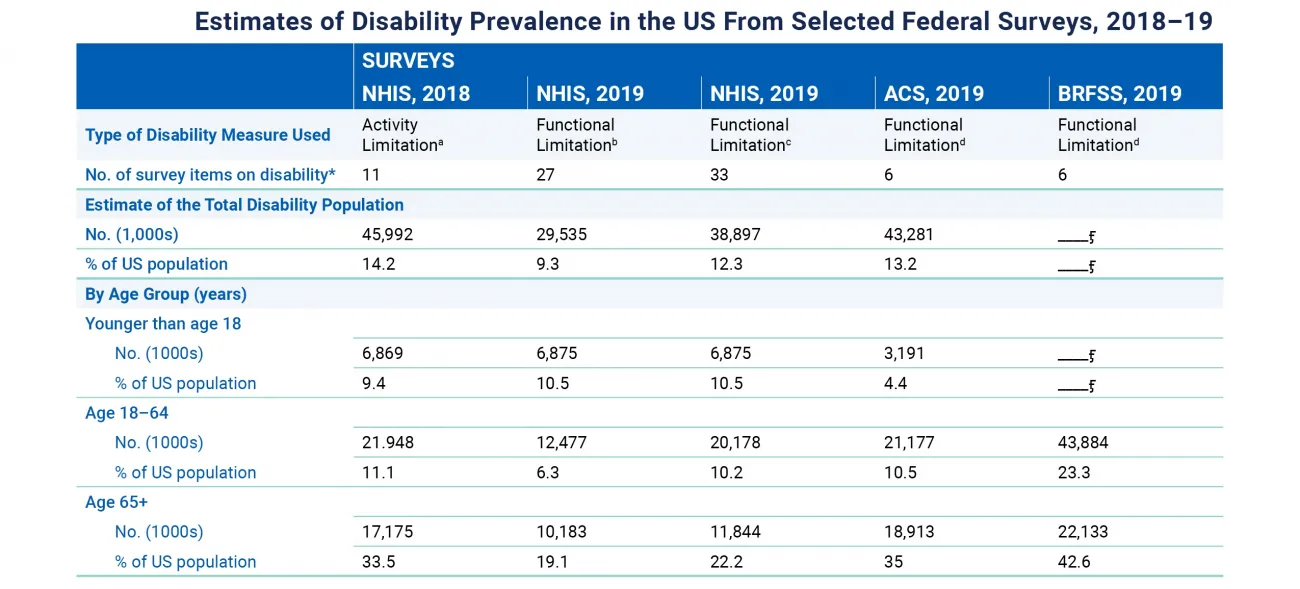

Figure 1, published in Health Affairs, highlights estimates of disability prevalence in the US from selected federal surveys between 2018-2019, which vary based on the definition of disability and the survey methods used. However, there is consensus that rates of disability are increasing as the US population ages, chronic conditions increase, and 1.2 million Americans live with long COVID-19 symptoms.

Figure 1: Disability Disparities

Definitions and designations are foundational to addressing disability health inequities

Definitions and designations are foundational to identifying and quantifying which groups of people face inequities and designating each group for specific federal and state regulations or programs that focus on payer and provider priorities.

What is a disability?

Disability can be defined in many ways, affecting issues like healthcare benefit eligibility and civil rights protections. Among federal statutory definitions of disability, a report found 67 different definitions.

The World Health Organization's (WHO) subscription to the biopsychosocial model conceptualizes disability as “an interaction between a person's functional impairments or chronic health conditions and the physical and social environment." This approach goes beyond the medical model that dominates healthcare today, defining disability “as an impairment or problem existing within the body or mind that can be identified by objective scientific or expert observations and ameliorated with the guidance or treatment of experts to help the person adapt and conform to the 'normal' environment."

How does health inequity intersect with disability?

The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) Secretary's Advisory Committee for Healthy People 2030 grounds our understanding of the unique healthcare experiences of individuals living with a disability.

Health disparities are defined as differences that adversely affect people with disabilities and are systemic and plausibly avoidable. Health equity is defined as the attainment of the highest level of health for all people through efforts to address avoidable inequalities, longstanding and current injustices, and health and healthcare disparities.

Considering the biopsychosocial perspective of disability—that occurs when a person with an impairment interacts with physical or social environments—health inequity happens when a person's disability is not considered in their care, their needs are not accommodated, or their known needs are met with hostility or discrimination.

What federal designation is essential to addressing the health equity needs of disabled persons?

Disability is a social construct and people living with disability are part of a marginalized group with unique histories and perspectives. Creating positive change requires specific designations.

Designating people with disability as a Health Disparity Population acknowledges that there is “a significant disparity in the overall rate of disease incidence, prevalence, morbidity, mortality, or survival rates in the population as compared to the health status of the general population." In consultation with the Director of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities (NIMHD) is authorized to make such a designation under 42 U.S.C. Section 285t(d)(1).

Not only would this designation provide federal protections, involve disabled people in federal health disparities research, and offer support for evidence-based policy changes, it would be an all-encompassing first step to recognizing the nation's largest marginalized group and rectifying enduring inequities.

What health disparities are linked to health inequity for the disabled population?

Andrés Gallegos, Chairman of the National Council on Disability (NCD), shared his vision and priority statement in 2021, focusing his tenure on “health equity as the predicate to people with disabilities being able to live, learn, and earn on an equal basis." He highlighted that discrimination against disabled people is pervasive and “well documented."

People living with disabilities are:

- 4 times more likely to report their health to be less than optimal

- 2 times more likely to be unemployed

- 2 times more likely to live in poverty

- 3 times more likely to have arthritis, diabetes, or a heart attack

- 5 times more likely to report a stroke, COPD, or depression

- More likely to experience injuries from intimate partner and interpersonal violence

- More likely to experience higher rates of chronic health conditions:

- diabetes (16.3% versus 7.2%)

- heart disease (11.5% versus 3.8%)

- obesity (30.2% versus 26.2%)

Individuals living with disability face additional social determinants of health (SDoH) and social risk factors due to higher-level needs. Meeting an individual's more unique or complex needs with appropriate accommodations adds other barriers that any health equity initiative must consider. Examples include a lack of wheelchair-accessible transportation or special nutrition not found in common food pantry programs.

When race or gender intersects disability

Compounding health inequity issues is when a person's disability intersects with another form of marginalization like race, gender identity, or other mental or physical disability.

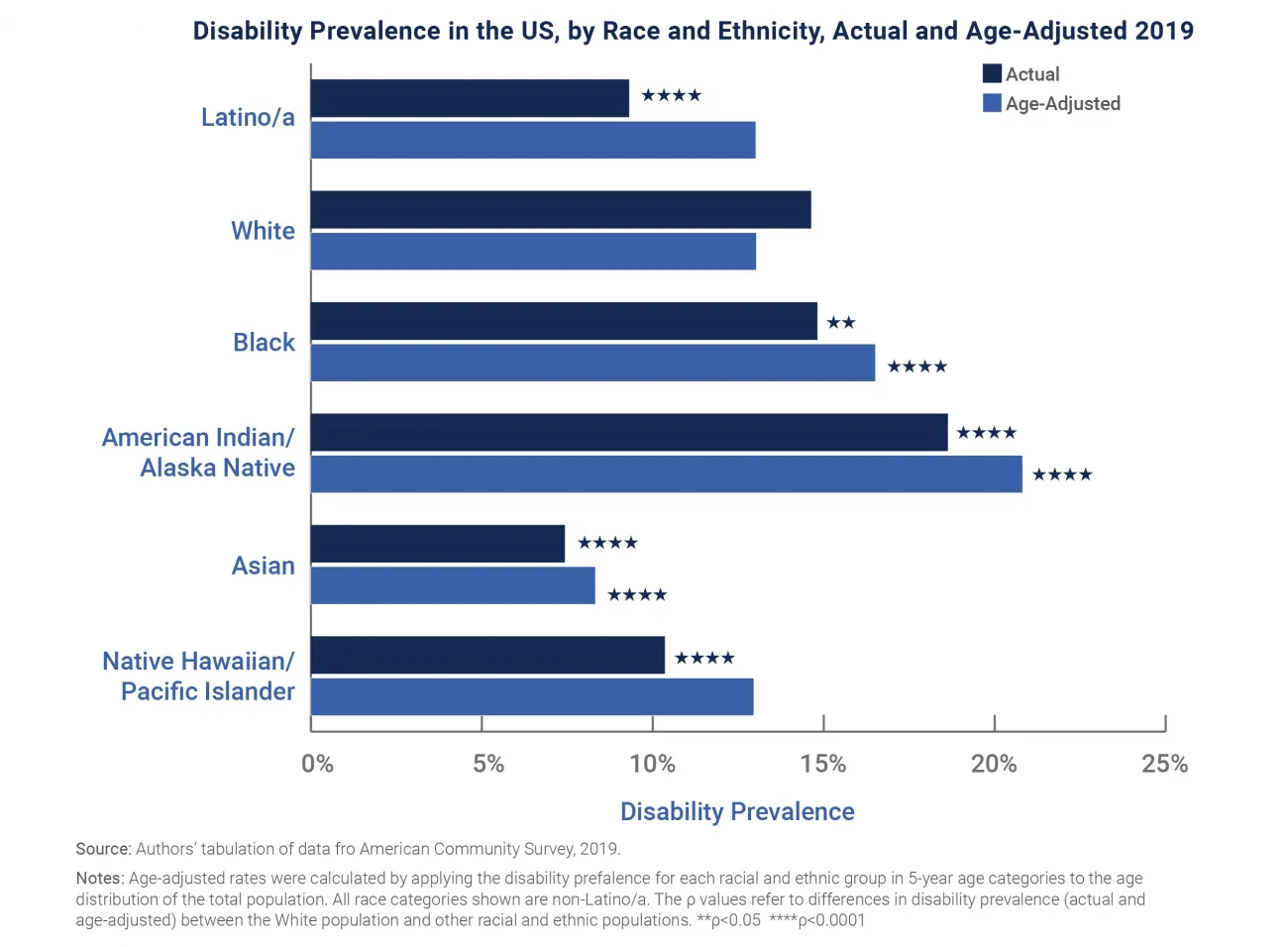

Figure 2, published in Health Affairs, outlines disability prevalence in the US, which can be compounded by class, race, ethnicity, religion, gender, age, or sexual orientation. This “double burden" is seen when race complicates disability health inequities.

- Blacks Americans with Down syndrome, for example, are more than 7 times as likely as White Americans to die by age 20. While the life expectancy for White people with Down syndrome is around 55 years, it's only 25 years for Black people with the same syndrome.

- When an individual lives with a disability and is part of a second marginalized community, they experience greater disparities than White individuals with disabilities.

- Adults with intellectual and developmental disabilities who identify as Black or Latino are likelier to report fair or poor physical and mental health than Whites with disabilities.

- Adults with mobility limitations from racial or ethnic minority groups are more likely to report worse health than a year ago.

- They are more likely to experience depression or have diabetes, hypertension, or vision impairment than White people with mobility impairments.

- LGBTQI+ individuals living with disabilities are more likely to report diminished health-related quality of life.

Figure 2: Disability Disparities By Race

Many race, gender, or other compounding factors create additional inequities and barriers to health, which are experienced through stigmas and stereotypes pervasive in healthcare.

Disability stigmas & stereotypes

Societal and personal assumptions, combined with a lack of professional training in disability competence, exacerbate health inequities. A national survey illustrates some misguided beliefs held by physicians:

- 82.4% thought people with a significant disability have worse quality of life than people without disabilities (contrary to research indicating those living with serious and persistent disabilities report good or excellent quality of life)

- Only 40% were very confident they could provide the same quality of care to patients with a disability

- Only 56.5% strongly agreed that their practices welcomed patients with a disability

Built on a history of harmful, discriminatory practices like institutionalization, involuntary sterilization, and medical rationing, many individuals living with disability see healthcare as a last resort for disease management or a forced source of potential harm.

Health equity for people living with a disability requires training and a person-centered approach

Uncovering bias, admitting the need for greater competence, and investing in health equity research and professional training are critical steps to seeing individuals living with a disability as unique persons with the right to realize their best health and quality of life. While their disability may pose complicating factors, delivering equitable and high-quality care means exploring the needs of each person and meeting them in great and small ways.

RTI Health Advance brings data science, social risk, and health equity research to bear

Our team of health equity, population health, and data science experts works collaboratively with payer and provider leaders who seek to deliver more equitable, higher-quality care to individuals living with a disability. Contact us to explore ways that we can help.

Subscribe Now

Stay up-to-date on our latest thinking. Subscribe to receive blog updates via email.

By submitting this form, I consent to use of my personal information in accordance with the Privacy Policy.